Women's media isn't always feminist - but it is becoming more political

On women's media, feminist journalism, and my eternal love for independent feminist media

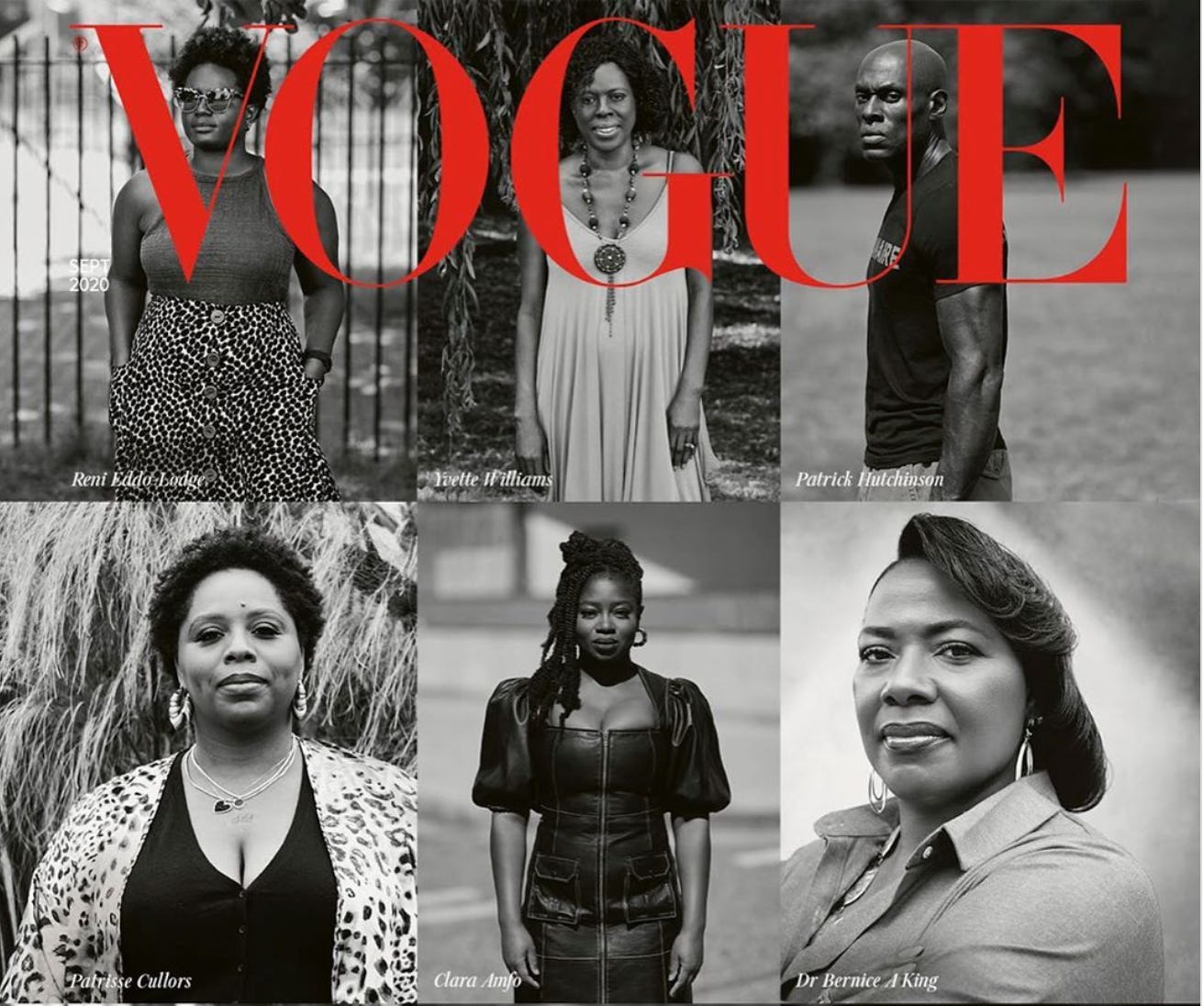

Photo: Vogue UK September 2020 issue

Recently, Vogue decided to do a series of September covers around the world loosely based on hope. It was historic; they had never before coordinated all 26 international editions of Vogue to work on the same editorial theme. In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matters protests and resulting discourse in the United States, many Vogue offices chose to feature more diverse covers and interview people about racial justice issues. Some covers were particularly notable, like Vogue UK’s, which was entirely dedicated to Black activists and the first cover in Vogue UK’s history to be shot by a Black photographer.

A friend of mine recently shared that he’s never seen so many Black women on the covers of women’s magazines in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter. I agree - and it’s been somewhat amazing to watch in real time mainstream women’s magazines and other mainstream publications attempt to do damage control to their reputations and cast, cast, cast, edit, edit, edit, and quickly revamp their editorial.

This has been happening for years, and some of this change has certainly been spurred by activist movements, and the rest has been led by the bottom line. Racial justice seems like the issue du jour when it hasn’t been centered before this moment, and it seems more than overdue. For several years now, I’ve noticed that different women’s media publications attempting to modernize and incorporate more politics, specifically feminist politics, into their issues. This isn’t altogether surprising, now that feminism is no longer largely regarded as a dirty f-word and has become mainstream.

Women’s media encompasses magazines, newspaper sections, podcasts, television, radio, movies and any other kind of media that you could possibly imagine that targets women - historically, cis hetero women - as their main audience. Women also tend to be the protagonists and media-makers (but not always) in these media platforms, but that isn’t always necessarily a good thing or representative: most women in media still tend to be White. And that makes an enormous difference in the nuances, perspectives, and intersectionality brought to issues that affect “women”.

Recently, I’ve seen something of what I consider a phenomenon: where media staff largely remain White, but they will bring in Black feminist ‘superstars’ as columnists or guest editors - Black feminists who are popular, well-known, by all means amazing, and have a built-in audience. This is something that I’ve seen women’s magazines in Brazil do over the past years. Black feminists who I respect deeply, such as Stephanie Ribeiro (Marie Claire Brasil), Luiza Brasil (Glamour Brasil), Joice Berth (Elle Brasil) and more. I’m thankful for the scholarship of Brazilian academics who are researching this phenomenon: how beauty and fashion columns in Brazilian women’s publications are making intersectional feminism and discourse available to the masses.

Part of me watching these developments over the years has been happy for these Black feminists’ much-deserved success and visibility. At the same time, I resent the fact that they perhaps wouldn’t have been offered these columns if they didn’t have a built-in following. Why aren’t staff in media institutions more diverse and hiring non-famous Black, Indigenous and women of color? Why aren’t more feminists editors in chief and re-designing entire editorial strategies like Elaine It definitely has something to do with the fact that there is systemic racism and gatekeeping in women’s media.

**

Check this: women’s sections in mainstream media publications have also sprung up. Initially, I thought this might be a good thing; the New York Times’ first ever gender editor job in 2017 seemed like it could signal much more coverage of feminist issues, gender, and sexuality. Ensuite, The Washington Post seemed to hire a gender editor almost immediately afterwards. The South China Morning Post, the largest regional news platform in East Asia, has also had its own gender outfit with Lunar, a newsletter about “celebrating Asian women and stories that matter”, for about two years now.

A New York Times piece about the death of independent feminist blogs across the United States tries to ring as somewhat positive: “To some degree, the sites were undone by their own popularity. Larger media organizations like The New York Times, The Washington Post and Condé Nast took notice of the rising generation of women journalists — and hired them. (The Times hired gender editors in 2017; The Washington Post has a gender columnist and a product called The Lily that is targeted at women.)”

Are we mainstreaming feminism by getting more “gender journalists” into mainstream publications, and making mainstream women’s publications more woke? I’m not so sure about that.

**

There are two types of media that can speak to the evolutions in the ways that I’ve read about, imagined, and began to create my own ideas about women, gender, sexuality, and feminism - women’s media and feminist media. The two are not the same and I certainly hope that they aren’t conflated as such - but there are all sorts of changes afloat in our rapidly changing media landscape.

Bringing in politics isn’t new - bringing in politics with an intersectional analysis and more visibility of racial justice is. But there have been people within mainstream women’s media who have been attempting to push forward feminist conversations for a while - trying to discuss domestic violence, reproductive rights, voting rights, history and much more. Yes, they were largely White feminists and writing about these lens from White feminist lens. But were they recognized and appreciated for the journalism that they did? It seems that women’s magazines still aren’t considered places for serious journalism today, and much less back then.

One aspect is certainly marketing. That also affects how readers and subscribers view these platforms. But another aspect is gender bias and internalized sexism about women’s issues in the media. Just because some women and female identifying people care about beauty - and hey, definitions and representations of beauty are changing - does that not mean that we can’t also be educated, intelligent, and hard-hitting in our politics? Britni de la Cretaz, a queer writer focusing on sports, gender and queerness, covered this in one of her newsletter editions about how attitudes towards politics writing in women’s media are still largely sexist today.

“Whenever a women’s publication runs content that is good or ground-breaking or radical, the response seems to be shock. We’ve seen this a lot with Teen Vogue’s political and labor coverage. It happens whenever Cosmo drops a huge investigative story (their reporting on reproductive rights is especially great). Refinery29 has had, for some time now, a phenomenal politics desk,” de la Cretaz writes.

Women’s media publications are a home for reporting that may not get greenlit elsewhere, simply because they cover issues that mainstream media publications do not consider important, hit-worthy or of public interest. And I’ve read incredible labor rights reporting from Kim Kelly on Teen Vogue, articles explaining reproductive justice from Elle, profiles of successful trans musicians on Vogue Brasil, and more.

One of the most common reactions that I get when I tell people that I’ve published something at Teen Vogue is their surprise - surprise that I would publish something there, surprise that Teen Vogue’s writing is ‘good today’, or surprise that Teen Vogue’s readers would even be interested in issues like this.

Today, some editors have changed their attitudes towards issues that they think interest women. “Ms. Holmes noted the change that has taken place since the early days of Jezebel, when her use of the word “feminism” in an early memo “set off alarm bells” at Gawker Media, as did her posting of a story on menstruation. Editors may have also adjusted their view of which stories are right for women’s publications. Stella Bugbee, the editor in chief of The Cut, the popular site that is part of New York Media, said web data shows that a reader interested in beauty products will also click on a political story. So The Cut runs “The Body Politic,” a column by Rebecca Traister, the author of “Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger,” alongside one by Daise Bedolla called “Why Is Your Skin So Good.””

Writing for Teen Vogue, I would realize that its Politics section is one of its least funded sections, even though it is award-winning, and I would say thoroughly feminist today. There was a reason why I wasn’t hooked on political writing in women’s media a decade prior - beauty, fashion, and celebrity gossip were always more heavily marketed than politics, identity, and other beats.

If feminist, political writing and reporting was systematically underfunded, undervalued, and pushed less than topics that seem more easily marketable to women such as beauty, fashion, and love, then most readers wouldn’t be interested in that. But were women making these kinds of marketing decisions? Feminists? I can’t imagine so. Look at the media oligarchies around the world and you’ll see decidedly unfeminist men at the top. Today, a new generation of feminist journalists, editors, and readers have at least succeeded in changing the editorial of some women’s magazines and other mainstream publications by letting them know: women and female identifying individuals can be interested in both fashion and feminism, and if you don’t change your editorial, you won’t be attracting and tapping into a newer, more progressive audience.

That’s why we should hold space for nuance and parallel existing realities. As feminists, we should be wary and critical of the misogyny directed towards women’s media, whether in the form of discrediting their reporting or beats, or belittling them for existing altogether, while at the same time recognizing that not all women’s media are feminist, intersectional, or good simply because they are written by or about women. Women aren’t a synonym for good, nor is all representation of gender (especially if it’s only representation of White women and other dominant ethnic groups) in media good, representative, or healthy. The normalization of traditional gender roles, toxic beauty standards, and other gendered stereotypes perpetuates the lived experience and expectations of gender, sexuality, and more that continue to damage countless lives around the world. We can hold mainstream media accountable for when it does perpetuate damaging representation to female identifying individuals while at the same time celebrating the mainstream women’s platforms that are getting it right - pushing the envelope on more inclusive, intersectional, and progressive identities, experiences, reporting, and art.

**

In large part, I think we should credit feminist journalists and independent feminist media for forcing larger conversations about feminist issues, representation, and politics. Today, we see platforms like the New York Times amplifying feminist philanthropy and the lack of funding going towards women of color who lead nonprofits, The Lily covering Hawai’i’s feminist economic recovery plan,Hyperallergic covering the Mexican feminists who occupied government buildings in protest, and more. I don’t think that feminist journalists are quite “owning” mainstream media as this Quartz article would have us believe, but I know that feminism becoming more accepted, feminist journalists advancing in their careers, and more mainstream media publications realizing that they need to cover gender, sexuality, and feminist issues more all make up this reality of more feminist news in the news today.

When I began to publish as a freelance journalist, I realized that I could share my research on feminist activism and movements to a much larger audience, and I've never looked back since. As a freelance journalist for the past 5 years, I know that my identity and position as a feminist journalist deeply connected to movements and activists separates me from most newsrooms. And as I never trained to be a journalist in a journalism school or academic institution, I was never forced to believe in the myth of objectivity in journalism.

In my relatively short career as a feminist journalist, I’ve met other feminist journalists and writers who have inspired me with their reporting and analysis, educated me, and continue to set the bar high for what I hope to achieve as a journalist and collectively as part of a movement. It turns out that when you’re a feminist journalist, you’re not really just trying to develop a career for your own individual professional success. If you’re a feminist journalist, then you already think of yourself as part of a larger movement. Your journalism is your activism. Your journalism is movement journalism, solutions journalism, movement archival and documentation, and feminist analysis that will become part of history.

Feminist journalism is a decisive action. Isabel Muntané says that feminist journalism is a radical, cross-cutting intervention: “Feminism is changing our perception of the world and this is a revolution. Communication is one of the most important, influential tools available for spreading and consolidating this process of change, and doing so through feminist journalism plays an essential role.

Using the gender perspective as a tool for feminist journalism, we can recover untold history, describe alternative realities and generate new meanings… Working from this standpoint means we reveal other realities and place them at the centre of information production from the moment we denounce and reveal the multiple inequalities of ethnicity, class, age, origin, abilities, sexual orientation and gender identification that configure intersectionality and which affect everyone to varying degrees. Thus it means giving a voice to everyone that mainstream media has consciously or unconsciously forgotten, placing forgotten topics, organisations and territories in the news’ agenda, thereby revealing the multiple discriminations of a sexist, racist and classist society. Above all, it means focussing information on people and human rights, above and beyond so-called authoritative institutions and voices. All we are doing, in itself a major task, is revealing discriminatory trends in a situation legitimised as natural.”

In this wondrously deep essay that I encourage all of you to read, Muntané also engages with what I’ve mentioned as the marketing, development, and creation of what today constitutes “women’s media”. Some things that are thought of as “women’s interests” still reek of assigned gender roles and gendered expectations. Muntané says, “Here is little point in a newspaper using inclusive, non-sexist language when it continues to assign fashion, motherhood and impossible body image, rather than politics, science and the economy, as women’s interests. Authoritative discourse and the voice of knowledge is no longer a matter inherent to men alone.” And I echo, there is little point in assigning Black feminist columnists to try to update archaic women’s magazines who still have 99% White staff and little feminist analysis in the rest of their editorial. It’s just marketing again, but instead of trying to persuade potential readers with lipsticks, you’re waving LGBTQI icons and prose about Black queer futures to try to entice them.

Muntané, again: “Although it is true that we are now seeing a change in media discourse, such progress is slow and littered with incoherence and contradiction. It is not a question of applying a feminist makeover or producing feminist specials on key dates, it is a matter of cross-cutting, radical intervention where women are the focus of news and we stop broadcasting sexist ideology through symbols that keep us in a feminised, private space.”

**

Much of this essay has focused on mainstream media thus far, but I would also like to state that this essay is a love letter to independent feminist media. I am HERE for you, feminist journalists, columnists, bloggers, essayists, filmmakers, podcasters, and other media activists. Your life’s work, sweat, tears, and words have been my school. I never took a single class about gender studies or feminism in high school or university; the internet, books, radio, music, TV, and films have all been my school for learning about feminist issues, much like many of you. And I know you gotta do whatever it takes to survive; I know that you fund so much of your work yourself, that you produce this media because it is essential to your being and survival.

In the last New Wave original essay, I wrote about how female leadership in capitalist, hierarchical, neoliberal, and authoritarian systems is not a feminist goal and never should be. “The master’s tools will not destroy the master’s house”, y’all.

But diverse, and specifically feminist, representation in media has a powerful effect that is still hard to put into words. I talk all the time about the danger and nuances of representation politics, but if there’s one kind of representation that is collectively powerful and mind-altering, it is representation in the media. Don’t give me a White female President who talks a lot about “women’s issues” with zero intersectional analysis or nuance, but please send me a collaboration between Kohl Journal and Al-Raida Journal on Decolonizing Knowledge Around Gender and Sexuality. Try to explain in words the life-affirming presence and truths of Blogueiras Negras, a Black feminist-run and edited platform, to tell Black feminist stories in their own words. Send me the gorgeously edited and shot Salty, a newsletter which is unabashed about pleasure, politics, and diverse bodies. The key difference with these feminist platforms is that diverse representation isn’t just the goal, but also diverse, queer, feminist, and loudly political creators, editors, illustrators, photographers, podcasters are front and center. When we get to tell our own stories, then the methodology itself becomes feminist, and perhaps our stories are less likely to be co-opted for the purposes of updating archaic, White-led institutions that ultimately don’t care about feminist liberation, but their own bottom lines.

When we see these images, and when we read these words, something changes in us. We think: oh, but we can be creators. We can literally create the worlds that we want to see. We don’t see journalism as being a distant possibility for us. We don’t see art as a distant possibility from ourselves. And we don’t believe that what we have to say and share isn’t unimportant anymore.

Independent feminist media is hard af to fund, if you’ll excuse my French. In my last New Wave interview with Ngozi Cole, we talked about the reality of young feminist-led and created media: “We’re producing a lot already, but there’s not too much monetary value attached to that. Either we’re doing the work for free, or we’re not being paid as much as we should.” Funders, please come find (some of) us, those of us who are looking for funding. We’re here, chugging along in the meanwhile.

**

I suppose my final considerations are: don’t be sexist about women’s media and dismiss good reporting when they do it. But also don’t consider women’s media to be inherently progressive because liberal feminism is the new trend of the day. Don’t perpetuate gender binaries, stereotypes and representation in the media, any media at all. Seek out feminist journalists, amplify and support their work. And above all, consume, support, and uplift independent feminist media, which is changing the conversations that we’re having, the way that we connect ourselves to larger systems and struggles, and serving as direct lifelines for our activism and goals for a different world.

I’m like a lot of other feminist media creators and activists out there: doing the work, underfunded, but fiercely independent and refusing to change our editorial for anyone. We are creating the worlds that we want to live in. And until those worlds exist, feminist media is how we are surviving, celebrating, and lifting each other up until we get there. To revolt is to dream and to create, and I hope that we all revolt.

**

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please send this to a friend to sign up and also promote on social media!

This newsletter is currently entirely free, so if you would like to support and buy me a coffee to fund my own independent feminist journalism and writing, especially in leading and developing New Wave, I’d be very grateful.

What I’m reading:

#EndSARS: Young Nigerians are leading the largest protests in more than a decade in Nigeria for the abolition of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (Sars) and the young feminist group Feminist Coalition was featured in the context of the anti-police brutality protests: “One such donation drive managed by Feminist Coalition, a weeks-old group of young Nigerian feminists that was formed in the wake of the protests, raised around $55,000 in four days through cash and bitcoin donations.”

Positive toxicity is terrible and annoying by itself already, but did you know that the narrative of ‘progress’ is also just destructive for progressive goals and organizing? Nesrine Malik writes about how talking about progress as an achievement can actually make it more difficult to spur real forward movement. If we want to understand our society’s progress, we need to change the way we speak about it.

The speed with which conservative values have reemerged among young women has been startling in China. Recent research indicates that rather than an increase in gender equality, which seems to be intuited as a byproduct of modernization, Chinese people have become more accepting of patriarchal gender norms.

Namibian feminists are leading the campaign against gender based violence and sexual violence in their country called #ShutItAllDownNamibia. You can read their official demands and more context about the campaign here.

AWID created a beautiful series of tributes to feminists and Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) who resisted the dominant economic system of exploitation and extractivism, putting forward powerful new #FeministEconomicRealities.

“Is bisexual the word for falling into the arms of trans people? Is bisexual the word for wresting nuance from binary? I am not sure. I am not sure about the accuracy of any language at all.” This essay about bisexuality by A.E Osworth for Autostraddle is beautiful, meandering, and a philosophical exercise.

Tensions as a way of being: I often revisit Kohl Journal’s summer issue on tensions in movement building and transformative justice. Transformative justice is about how entire communities can radically address violence as structural without cancelling each other, by going beyond individual and isolated blame.

Pro-women and anti-worker: nothing more disgusting than some damn outright hypocrisy. Anti-union feminist organizations are just that. One of my favorite labor rights journalists Kim Kelly has written this piece for The Baffler about the anti-union organizing at reproductive rights organizations.

"When we see these images, and when we read these words, something changes in us. We think: oh, but we can be creators. We can literally create the worlds that we want to see." Really needed to hear this!! Made me look back on my teenage years and everything I was reading and how I felt about it. Like i really grew up on independent feminist blogs on the internet but always coded them in gendered terms because internalized misogyny. But these were also central to my growth and pushed me think about politics and music and etc in ways that mattered to me and other young girls. But also, a lot of these spaces were run by White feminists and couldn't fully represent what I wanted/needed to see (v grateful for Rookie mag but they had a TYPE idk)

So when you write about envisioning against the grain it made me think about how we've always already been capable of creating what we need. <3 <3 <3

This resonates so deeply + is creating ripples of change through physical and digital realms. Thank you for your voice and leadership and incredibly thoughtful prose and journalism. It is an antidote and guiding light in these chaotic times.